Fundamental shifts in the role of the architect

Historical observation of change in the role of Architects

In his 1998 book, The Favoured Circle, Garry Stevens set out to understand and define the ecology of the field of architecture, specifically as related to those considered to be elite architects. Using a tool-set based on Bourdieu understanding the book sought to first establish the field of architecture and then, having done so, to expose the ‘social foundations of architectural distinction’.

The book is underpinned by a major piece of research in which Stevens reviewed the Macmillan Encyclopaedia of Architects (MEA) (1) and used this to create his Vasari Database.

The information Stevens was able to derive from the database is both extensive and illuminating, and as a result the book is overflowing with fascinating observations. Any number of which would be worthy jump off points for expansion and further study in their own right.

One notable example being the revelation that at any one moment in history 25% of eminent architects that have ever lived are alive. For the elite architects (the best of the best) this ratio drops to 1 in 6. Stevens compares these figures with the field of science where 45% of eminent scientists are alive at any moment. The implication of this is that architecture as a discipline is dominated 3 to 1 by luminaries from its past.

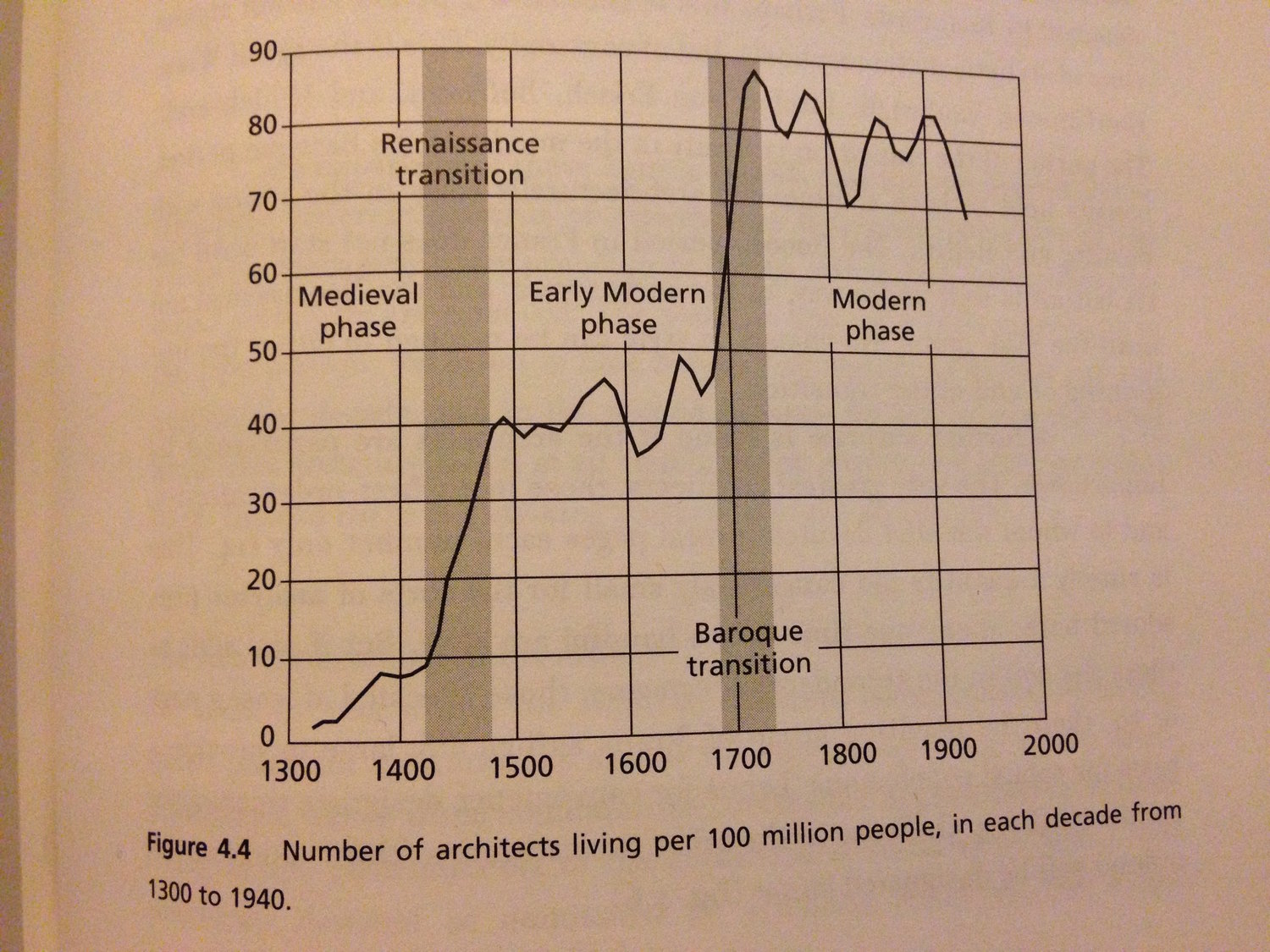

I encourage everyone in the field of architecture, especially those setting out on architectural studies, to read the book, but this point I feel in danger of simply retelling the findings of Steven’s work with minimal transformation. I will therefore now focus on a key finding to emerge from the study which is of particular interest to me, namely the observation that the number of significant architects living per 100 million people experienced sudden and significant growth on two separate occasions.

[Garry Stevens, 1999. The Favored Circle: The Social Foundations of Architectural Distinction. Edition. The MIT Press.]

Looking closely at these time frames Steven’s identifies overlaps between the explosion in numbers first with period of the Renaissance transition, and then secondly with the urbanisation of Northern Europe. These periods relate directly to findings by M. S. Larson in Emblem and Exception: The Historical Definition of the Architect's Professional Role (2) as the historical moments that the definition of the role of the architect is found to have fundamentally changed.

To summarise Larson’s extensive and ground breaking work:

Pre-renaissance the architect is almost anonymous, a master builder completing the work as defined by the client;

Post-renaissance the architect becomes the creative genius and they are in control of the development of style;

Post-Baroque the architect transitions into the role of expert.

From this work it’s clear that the practice of architecture in the Western context is currently in it’s third era. My question then: is the disruption outlined above purely an historical artefact, or will fundamental change to the role of the architect happen once again? If so, are we currently in a period of stability, or the foothills of more change?

Evidence of contemporary shifts

The evidence presented suggests that during certain periods of major social change significant changes to the role of architects also occurs, I assert that there is reason to consider whether (or not) profound social change is happening once again.

2016 seemed to be a case study year in ongoing shifts in the western world. In the year just passed the accepted norms of politics were seemingly redundant and polls were left confounded. With OED naming ‘post-truth’ as its word of the year, the year seemed to be characterised by a rejection of experts - particularly worrying for architects, who have an entrenched perception of their role as that of the professional expert.

If voting in the UK and US in 2016 sharply brought the political element of social change into focus, perhaps Tom Goodwin best articulated social change as manifest in business when in 2015 he famously observed:

Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate. Something interesting is happening.

While these examples again deal with observation of events after the fact, we can go back to the work of Alvin and Heidi Toffler in which they predicted an era of rapid and constant changes in society which individuals would struggle to assimilate to, and coined the phrase for this experience which titled their 1970 book - Future Shock.

At this juncture it is worth noting that I am not suggesting that every moment of social change has lead to fundamental shifts in the role of the architect, but having established that we are seeing evidence of social change, it is worth looking for corresponding changes in the practice of architecture.

Focusing now on the context of architecture in the UK. Recently the profession has been grappling with the emergence of technical innovations such as BIM its impact on workflow and design team composition and relationships. Concurrently the initial emergence and subsequent dominance of D&B contracts, and the current industry push toward partnering contracts again indicates a significant and fundamental shift in the location of the architect to the act of construction. As a response to these developments, and in an effort to grapple with changing work flow in the construction industry, in 2015 the RIBA made significant alterations to its prescribed Plan of Work.

In the UK the shift of architecture to the position of experts as defined by Larson, was enshrined through the creation of appropriate gatekeeper institutions, namely RIBA as professional body, and the university School of Architecture system. A shift away from this role would expose these incumbent structures to disruption, and potential dissolution, so it is natural then that such institutions established on conservative principles to ensure stability, should attempt to alter the perception of change, and to draw it in line with their own epistemology.

The fact is that evidence of cracks in the establishment of architecture can be seen at least as far back as the 1980s work Donald Schön, who cited the inspiration to undertake his, now seminal, analysis of architecture pedagogy as ‘the crisis of the professions’; termed as the inability of professions to maintain a stable and obtainable amount of knowledge in the face of rapid growth of complexity resulting from modernisation and industrialisation.

Towards the forth era of architecture

Having identified the impact a social change historically has had on the role and practice of architecture, there is certainly enough initial evidence to consider that society is once again in the midst of such a fundamental change. This is matched by more than enough evidence of change manifesting in practice of architecture to justify further investigation.

What is left is to look at is where this change might be taking us, and more pressingly, how emerging disruption will manifest along the way.

-----

Footnote (1)

The production of the MEA was in itself an extraordinary undertaking. The publication consists of 4 volumes with more than 2,400 pages total. It contains over 2,600 biographies, written by more than 600 contributors from 26 countries. Biographies span from 1400 - 1980 and cover the western world.

[Garry Stevens, 1999. The Favored Circle: The Social Foundations of Architectural Distinction. Edition. The MIT Press.]

Its broad contribution profile and peer reviewed content ensures its validity as a source for the study due to the Bourdieu criteria that a field is self defining. Stevens also found that the MEA was an appropriate source for quantifying which practitioners the field considers elite as both ‘the editor-in-chief and senior editor explicitly stated each biography length was directly dependent on each architect’s assessed importance.

Footnote (2)

While Steven’s study was completed nearly 20 years ago, using a source which is now nearly 30 years old, there are limitations to the usefulness of simply repeating the methodology of his study to produce more up to date information in the hopes of answering my questions.

As it is produced by historians, the MEA is a lagging indicator of the field, therefore a significant time would have to have passed from any fundamental change before the effects would be captured in a source of this type.

The scope of the original study was the western world and picked up on two major shifts in global power, to complete the study now perhaps a different global area must be considered, putting the continued usefulness of this initial data in doubt.

If the fundamental role of the architect changes this new role might not currently be engaging with the existing professional mechanisms, so identifying them through professional registration might not currently be possible.

Links

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-38402133

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2016/aug/08/rejection-of-experts-spreads-from-brexit-to-climate-change-with-clexit

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-the-year-2016

https://techcrunch.com/2015/03/03/in-the-age-of-disintermediation-the-battle-is-all-for-the-customer-interface/